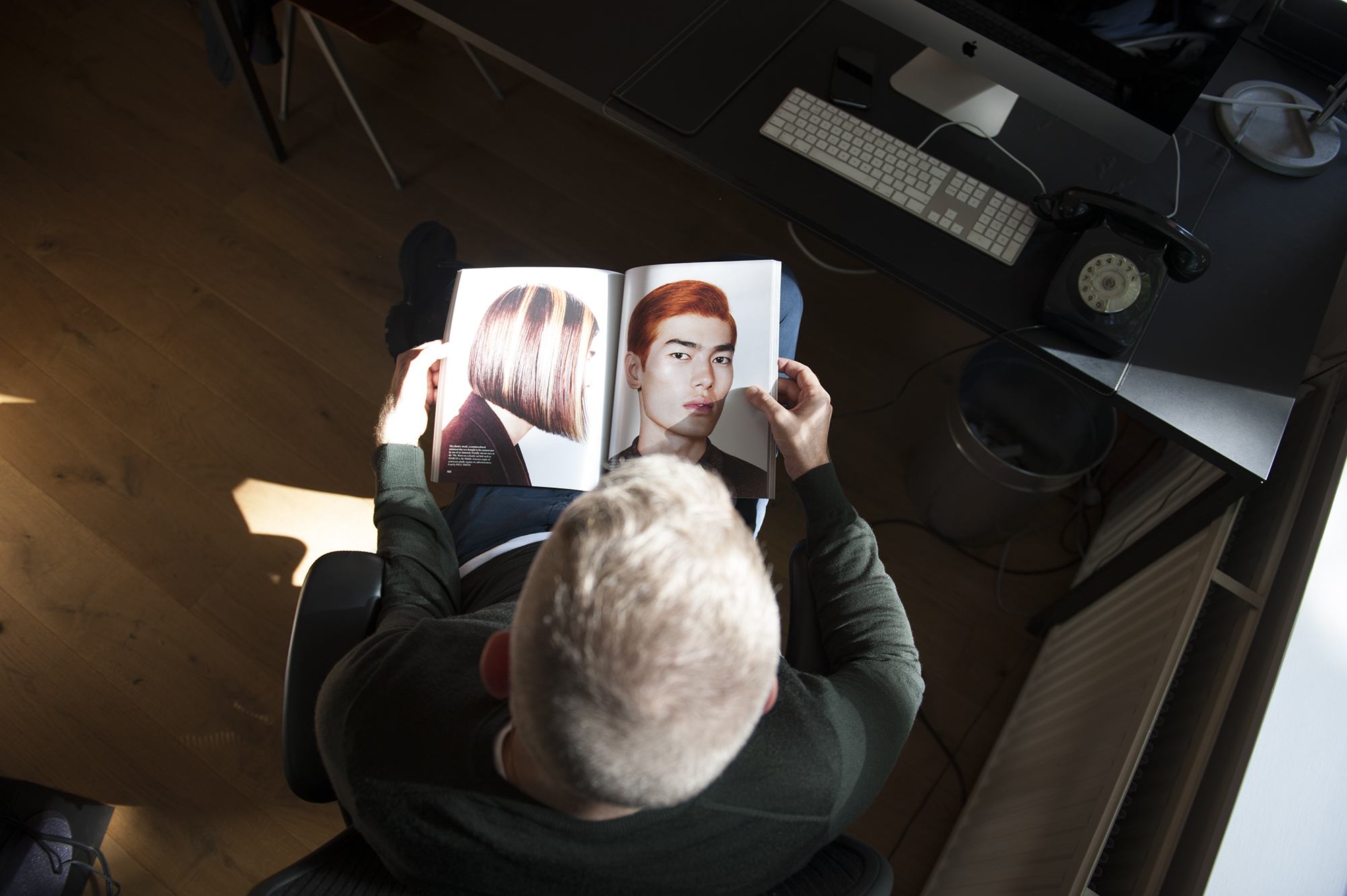

The Paper Issue. Interview:

Gert Jonkers, Editor-in-Chief of the Fantastic Man

The Paper Issue. Интервью:

Герт Йонкерс, главный редактор Fantastic Man

One of the pillars of independent publishing, Fantastic Man revolutionised the fashion magazine world after its inception in 2005. Its editors eschewed the classic men’s magazine matrix — women, cars, sports — in favour of long features, controversial topics, unconventional models and a black-and-white colour scheme. Despite its slow pace (the magazine is published twice a year) Fantastic Man has maintained a striking sense of relevance to the here and now. Although known as a publication for men, the magazine is enjoyed by both genders. Fantastic Man’s founders, Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers, a publishing duo from Amsterdam, had previously run the (now defunct) gay culture periodical Butt. Apart from Fantastic Man, theycurrently publish the elegant women’s title The Gentlewoman, as well as COS magazine, a seasonal edition for eponymous Swedish fashion brand, and The Happy Reader, a digest produced in partnership with Penguin. Exclusively for The Blueprint, Gert Jonkers talks to Jana Melkumova-Reynolds, Editor-at-Large of WeAr, a quarterly magazine aimed at fashion professionals worldwide.

Один из столпов в мире независимого издательства — Fantastic Man произвел тихую революцию в мире журналов. Его редакторы избегали классических шаблонов мужских изданий (женщины, автомобили, спорт), не боялись длинных текстов, неочевидных тем, моделей немодельной внешности и черно-белых страниц. Несмотря на старомодную медлительность и периодичность раз в полгода, Fantastic Man всегда оставлял ощущение актуальности сегодняшнему дню. Этот мужской журнал в равной степени любят представители обоих полов, а выпускает его дуэт издателей из Амстердама, на счету которого также ныне закрытый гей-зин Butt, элегантный The Gentlewoman, регулярное издание для сети магазинов COS и совместный с Penguin дайджест The Happy Reader. Специально для The Blueprint с одним из главных редакторов, Гертом Йонкерсом, встретилась Яна Мелкумова-Рейнолдс, главред профессионального фэшн-журнала WeAr.

Click here to change the language

ВОПРОСЫ: ЯНА МЕЛКУМОВА-РЕЙНОЛДС

ФОТО: САША ЗАЛ

INTERVIEW: JANA MELKUMOVA-REYNOLDS

PHOTO: SASHA ZAL

First question: why are there so many magazines from Holland?

Are there many magazines from Holland? I hadn’t realised that. But Holland has a very long graphic design history. Together with the Swiss, the Dutch graphic designers and typographers are some of the best in the world. There has always been a love of print, and the education has always endorsed it, particularly Arnhem [ArtEZ University of the Arts], but also others. Besides, Dutch is such a small language that a lot of publications from Holland decide to go English, while French or Italian magazines are more likely to be published in French or Italian (Purple and Self Service excluded). The Dutch aren’t particularly sentimental about their language. So it might seem that there are many international Dutch magazines, although in reality there probably aren’t any more Dutch than French or Italian ones.

— Хотелось бы начать вот с чего: почему именно в Голландии выходит так много журналов?

— В Голландии выходит много журналов? Никогда об этом не задумывался. Хотя у Голландии долгая история графического дизайна. Наряду со швейцарцами, голландские дизайнеры — одни из лучших в мире. Здесь всегда любили печатную продукцию, и в образовании это направление поддерживалось, особенно в университете искусств ArtEZ в Арнеме, но не только там. Ну и потом голландский язык не особо распространен — и множество изданий в Голландии выходят на английском, тогда как французские или итальянские журналы, скорее всего, будут выходить на своих родных языках (за исключением Purple и Self Service). Голландцы легко относятся к своему языку. Поэтому и возникает впечатление, что кругом очень много международных журналов из Голландии, хотя в реальности, скорее всего, голландских не больше, чем французских или итальянских.

Which brings me to my question about language. I, too, edit a magazine that is published in English – not the first language for the majority of my editors, me included – and distributed in 60 countries. It is truly international, and, for this reason, I feel enormous pressure to write in plain, simple English that would be accessible to non-native speakers. Now, you seem able to successfully resist this pressure to simplify, although you also cater to many non-English speakers (most magazines do these days), and are not native yourself. I find it really curious that Fantastic Man is – not that it’s arcane, but it uses long, complex phrases and a sophisticated vocabulary; it is for someone who likes reading, rather than skim-reading. How did you come up with this format, and who is it for?

It’s a bit of a cliche to say this, but it’s very much for ourselves. We didn’t have a clever business or marketing plan; we didn’t sit through focus groups and decide “Okay, this is our target audience…”

— Что наводит на вопрос о языке. Я тоже редактирую журнал, который выходит на английском — неродном языке для большинства моих редакторов, включая меня, — и распространяется в 60 странах. Это на самом деле международное издание, и по этой причине я чувствую, что должна писать на простом английском, чтобы тексты были понятны неанглоговорящим читателям. Вы же не пытаетесь ничего упрощать, хотя также пишете для огромного количества людей, для которых английский не родной язык (как и большинство журналов сейчас), да и для вас он не родной. Мне кажется любопытным, что Fantastic Man не боится использовать длинные, сложные фразы и затейливый вокабуляр, он для читателей, которые любят читать, а не скользить по тексту. Как вы пришли к такому формату? Для кого он?

— Это, конечно, клише, но мы все делаем для себя. У нас не было никакого бизнес- или маркетингового плана. Мы не сидели на фокус-группах и не рассуждали: «Ну что, это наша целевая аудитория…»

— Никаких фокус-групп?

You never had any focus groups at all?

No. Anyway, I have friends and family in Holland who say “I find Fantastic Man difficult to read”. And not only friends and family: every now and then a new intern comes in and starts using these very elaborate words, thinking that’s what we want to see – and I immediately cross them out, because you can say most things in a normal way. I like the language to be beautiful, but not deliberately difficult. I don’t like sentences cluttered with unnecessarily lengthy constructions or words no one knows.

— Нет. При этом у меня в Голландии есть друзья и родственники, которые говорят: «Мне сложно читать Fantastic Man». И не только друзья и родственники — периодически приходит новый интерн и начинает использовать заковыристые слова, будучи уверенным, что мы хотим именно этого, а я их сразу вычеркиваю, потому что большинство смыслов можно выразить проще. Мне нравится, когда язык красивый, но не намеренно сложный. Не люблю, когда предложения перегружены ненужными длинными конструкциями или словами, значения которых никто не знает.

— Так как же сформировался этот язык?

So how did this language come about?

As we started Fantastic Man there was a classic – not retro or historic but a very classic look and feel to it – and the language came from it. We were inspired by GQ from the 1970s, or the way Vogue used language around that time. If you look at them now, some of the captions appear ridiculously long – up to 900 words, which these days is considered to be a relatively long article!

— В самом начале Fantastic Man по виду и ощущению был очень классическим. И язык был такой же. Нас вдохновил GQ 1970-х и то, как пользовался языком Vogue того же периода. Если сейчас посмотреть на эти журналы, то можно, например, обнаружить подпись под фотографиями по 900 слов — по сегодняшним меркам это довольно длинная статья!

— Да, в моем журнале 450 слов — это лонгрид.

Yes! In my magazine, 450 words is a long read.

But if you look at Vogue from 1975, the captions are 400-500 words, it is the norm.

— А в каком-нибудь Vogue 1975 года кэпшен в 400–500 слов — норма.

— Ну, у вас они тоже длинные, и в них есть нарратив: «Томмазо смотрит на горизонт в рубашке Margiela» — вроде того. Это один из фирменных приемов Fantastic Man, так же как и то, что вы обращаетесь к читателю «мистер».

— На самом деле уже нет. Слишком много других редакторов взяли его в оборот, и нам стало скучно. Но мужчинам действительно нравится некоторая формальность, они любят обращаться друг к другу в такой манере. А вот с женщинами это не работает — для The Gentlewoman нам надо было придумывать совершенно другую интонацию.

Yours are long too, and they have a narrative, don’t they? “Tommaso is looking at the horizon while wearing a Margiela shirt”, things like that. This is one of the signature Fantastic Man quirks for me, just like the fact you address your readers as “mister”.

We don’t anymore, actually. Too many other people started doing it, and we grew bored. But men do like a certain formality, they have fun addressing each other in this way. This doesn’t work with women, though – we had to come up with a different tone of voice when we started The Gentlewoman.

It’s a bit of a cliche to say this, but it’s very much for ourselves.

Это, конечно, клише, но мы все делаем для себя.

For a start, should it be Mrs or Miss for a woman? When you make this choice you classify the women by whether she is married or not, and that’s terrible. In any case, if you say “Miss Paley is opening her gallery” it sounds awful. She’s Maureen! It’s not “Ms Otto”, it’s Karla. With women it somehow makes more sense to speak on first name terms.

— Почему?

Why?

— Для начала — это должна быть «миссис» или «мисс»? Делая подобный выбор, вы классифицируете женщин по признаку ее матримониального статуса, а это ужасно. В любом случае, если вы напишете «Мисс Пейли открывает галерею», это прозвучит странно, потому что она Морин! И не «мисс Отто», а Карла. С женщинами почему-то приятнее пользоваться именами.

— И все-таки сколько читателей понимают эти тонкости? Особенно неанглоговорящих читателей?

How many people pick up on the fact that the inner lining of your jacket is made of horse hair? I don’t care who picks up. You won’t say “no one will notice there are typos – let’s not budget in a proof reader”, that’s not even a conversation. And Fantastic Man for us is not an exercise in cost-effectiveness.

— А сколько людей понимают, что бортовка для вашего жакета сделана с добавлением конского волоса? Мне все равно, кто понимает. Вы же не будете говорить: «Никто не заметит опечатки — давайте сэкономим на корректоре», об этом даже речи не идет. Мы в Fantastic Man не занимаемся эффективным сокращением расходов.

How many readers pick up on this though? Seeing that they are non-English?

I guess no print magazine is these days. You spoke of the love of print earlier. Have you ever been tempted to go digital and forego the material side of publishing?

No. I don’t have much of a connection with the digital, even though over time I grew more used to it. I grew up without the Internet. We like the magazine as an object. We are a biannual publication, we have a 6-months cycle, so we can afford a 3-week period when everyone sits together in a room, and it’s almost like sculpting. There are lots of publications where the editor just sends off the texts and images to a designer who sits in the other end of the country…

— Думаю, как и другие печатные издания в наши дни. Вы говорили о любви к печатной продукции. Никогда не было соблазна уйти в диджитал и отказаться от физической стороны издательства?

— Нет. Я не ощущаю связи с диджитал, хотя с течением времени привыкаю. Я вырос без интернета. Нам нравится журнал как объект. Мы выходим дважды в год, у нас цикл — шесть месяцев, так что вполне можем позволить себе три недели сидеть вместе в одной комнате. Это практически как скульптуру ваять. Есть много изданий, где редактор отправляет текст и картинки дизайнеру, который сидит на другом конце страны…

А 3-week period when everyone sits together in a room, and it’s almost like sculpting.

Три недели мы сидим вместе в одной комнате.

Это как скульптуру ваять.

Or in a different country – that’s what we do at the magazine I edit. I’ve never met most of my editors in person, everyone is in a different time zone, and my graphics team is a 2 hours flight away from me. And you physically sit in a room! How nostalgic.

— Или вообще в другой стране — так устроен мой журнал. Я никогда не видела большинство своих редакторов, все в разных часовых поясах, а мой дизайн-отдел в двух часах лету от меня. А вы физически сидите в комнате! Это так старомодно.

It’s a very material thing: the whole magazine is lying on the floor, and nine people walk around it saying “the page order isn’t completely right” or “if this section opens with a big portrait, will it feel repetitive if the next one opens with a big portrait too?” It’s a very sensual, tactile process. People are stepping over and taking out pages, and someone says “if this piece was 1000 words shorter it would feel much better”, and suddenly it all makes sense.

— Это осязаемо — весь журнал лежит на полу, вокруг ходят девять человек и говорят: «Порядок страниц не совсем правильный» или «Если этот материал открывает большой портрет, не будет ли повторением следующий с большим портретом?» Это физический, тактильный процесс. Люди наступают на страницы, вынимают их, кто-то говорит: «Если бы этот материал был на 1000 слов короче, я бы был спокойнее», и вдруг все приобретает смысл.

— А вы как-то ощущаете всеобщую диджитализацию медиа? Это вдохновляет вас, пугает? Меняется ли журнал? В конце концов, мир сильно изменился с 2005 года, когда вы запустили Fantastic Man.

Have you been feeling influenced by the digitisation of media lately? Threatened, inspired, perhaps? And has the magazine changed a lot? After all, the world now is a very different place from 2005, when you started Fantastic Man.

— Я не думаю, что мир сильно изменился с 2005 года. И не согласен, что он стал более цифровым. Тогда существовал Friendster, а мы пользовались электронной почтой.

I don’t feel the world has changed much since 2005. I don’t think it’s that much more digital. Friendster existed back then and we were using email.

But there was no Facebook and no Instagram, and I remember how fashion brands didn’t want to sell to Net-a-porter because it was an online retailer. That wasn’t even 2005 – it was 2009, maybe even 2010.

True. But no, we haven’t been influenced by the digital shift. Weirdly, not so much has changed for us generally! I guess the feeling of the magazine may have changed – it was maybe more black-and-white. It became more modern.

— Но не было ни фейсбука, ни инстаграма, и я помню времена, когда фэшн-бренды не хотели продавать одежду в Net-a-porter, потому что это онлайн-магазин. Это еще в 2009–2010 годах было.

— Верно. Но нет, на нас перемены в сфере диджитал не повлияли. Удивительным образом для нас самих тоже не так уж много изменилось! Пожалуй, изменилось ощущение от журнала — он стал более черно-белым. Более современным.

— Почему вы перестали выпускать Butt (гей-журнал, одно из первых изданий Йонкерса. — Прим. ред.)?

Why did you stop Butt [a gay magazine, one of Jonkers’ first publishing ventures]?

For me there were 2 reasons. Firstly, at some point I was asking a lot of questions about sex…

— По двум причинам. Во-первых, в какой-то момент я понял, что задаю очень много вопросов про секс…

— И вы уже знаете все ответы?

And then you found all the answers?

Sort of, yes, I couldn’t come up with the same curiosity. And secondly and mainly, we stopped because of the Internet.

— Вроде того, да, любопытство мое уже не было таким острым. Во-вторых и в-главных, мы перестали выходить из-за интернета.

— Ага!

Aha!

Butt was not so easy to find — not deliberately rare, but we didn’t want to advertise, we didn’t do poster campaigns because we didn’t want to put it into people’s face.

— Butt было не так легко найти — это не специально, просто мы никак не рекламировали его, не давали наружную рекламу, вообще не хотели тыкать им людям в лицо.

It was a bit of a zine in that sense.

Yes, you had to discover it, and if you did not want to discover it you would not. Some people weren’t interested in it, and that’s fine, because it was for a very particular interest group – in fact, it’s amazing that it became much more legendary than we had ever imagined. It was niche, and we had very open candid conversations with people. The approach of the magazine was quite radical because these conversations were very long and very literal. The interviews usually started with “Is the tape rolling?” and really felt like a literal transcript of a good conversation you were sitting in on. But when Internet publishing and social media took off, we couldn’t be so secret anymore, and I couldn’t expect the same openness from the people I was interviewing. There are things I would love to talk about face-to-face with somebody, but I wouldn’t expect that conversation to be visible to the whole world. Yet at some point our articles started appearing online – sometimes we published them, but in a lot of cases readers painstakingly typed them over and put them on their blogs, because they thought they were interesting. And then some interviewees started saying “I’m OK with having this in the print issue, but I wouldn’t want my parents to read this”. This is fair enough, people are allowed to have secrets, and I am not the person who wants to unveil them – I don’t want to be a gossip journalist.

— В этом смысле он скорее был зином.

— Да, надо было самому его находить, а если кто-то не хотел его видеть, он его и не видел. Не всем этот журнал был интересен, и это нормально — он создавался для очень небольшой группы людей, и, на самом деле, это совершенно невероятно, что он стал таким легендарным. Это было нишевое издание, в котором мы говорили с людьми очень открыто. Подход был довольно радикальный, так как разговоры были очень долгие и литературные. Интервью обычно начинались с фразы «Диктофон записывает?» и ощущались скорее как транскрипция вдумчивого разговора, при котором вы присутствовали. Но с развитием интернета и соцсетей мы перестали быть тайной и уже не могли ожидать такой же открытости от людей, с которыми говорили. Есть вещи, которые я люблю обсуждать один на один, и не хочется, чтобы разговор был доступен всему миру. В какой-то момент наши материалы стали появляться онлайн — иногда мы сами их публиковали, но часто читатели тщательно перепечатывали их и размещали в блогах, потому что считали их интересными. И некоторые наши герои стали говорить: «Пусть это появится в печатном издании, но я не хотел бы, чтобы мои родители прочитали это». Это справедливо, у людей должны быть секреты, и я не тот человек, который хотел бы их раскрывать, — я не хочу быть желтым журналистом.

— Получается, что через интернет Butt добрался до людей, которые не были вашими читателями изначально, а это не всегда хорошо?

So through Internet Butt started reaching people who weren’t your original readership, and that was not always a good thing?

Yes. Of course, in a way, it was a good thing – for example, we didn’t know how to go about distribution in South America, and the Internet brought us a lot of readers from that part of the world. Basically, in beginning we figured we knew Paris and the 4 bookshops we wanted to be in, same for Stockholm, Vienna, Amsterdam and London; then someone came along who could place us in gay stores in Chicago and Detroit. But there hadn’t been mass distribution, and then with the advent of the Internet suddenly there was. Some of our interviewees started getting stalked. I didn’t want any of these dark things. We closed Butt in 2012.

— Да. Конечно, в каком-то смысле это было хорошо: например, мы понятия не имели, как построить дистрибуцию в Южной Африке, а интернет привел к нам много читателей из той части мира. Поначалу мы рассчитывали на Париж и четыре книжных, в которых мы хотели продаваться, то же в Стокгольме, Вене, Амстердаме и Лондоне. Потом появился кто-то, кто смог разместить нас в гей-магазинах в Чикаго и Детройте. Но массовой дистрибуции никогда не было, а с развитием интернета она вдруг появилась. Кто-то из наших героев подвергся преследованиям. Я никогда ничего такого не хотел. Мы закрыли Butt в 2012 году.

— Читатели Fantastic Man пересекаются с Butt?

— Немного. Мы запустили Fantastic Man, потому что подумали, что многие читатели Butt хотели бы чего-то другого, чего-то, чего не было в Butt, потому что мы не хотели превращать его в фэшн-журнал.

Does the readership of Fantastic Man overlap with that of Butt?

A little bit. We started Fantastic Man because we thought a lot of readers of Butt would be interested in something else, something we weren’t featuring there because we didn’t want to make it into a fashion magazine.

But is Fantastic Man a fashion magazine?

Well, yes, I guess. I don’t know how to describe it.

— А Fantastic Man — это фэшн-журнал?

— Думаю, да, хотя критерии расплывчаты.

Can you read a fashion magazine? I do look at fashion magazines.

А разве можно читать фэшн-журналы? Я их смотрю.

Do you read fashion magazines?

Can you read a fashion magazine?.. I do look at fashion magazines. I respect what other people do. I like to look at Purple, I like to look at Self Service, I like to look at Dust.

— Вы читаете фэшн-журналы?

— А разве можно читать фэшн-журналы? Я их смотрю. Я уважаю чужую работу. Я люблю смотреть Purple, я люблю смотреть Self Service, я люблю смотреть Dust.

— Что мне нравится в Fantastic Man — что в нем до сих пор есть что-то от зина: отсутствует боязнь длинных текстов, множество тем, которые не то чтоб понравились бы гипотетическому рекламодателю. Например, советы, как не переплачивать за багаж, когда летаешь лоукостерами, — я хочу сказать, что лоукостерами летают все, но это не то, про что ты рассчитываешь прочитать в глянце.

— Мы не глянец. Фэшн-журнал, да, но не глянец. Мы обожаем одежду, а это не то, про что мужчины говорят очень часто или очень легко. Мы недавно запустили новую рубрику, «Викторина», где обсуждаем с мужчинами их гардероб. Пока там короткие вопросы, но они могут развиться в длинные. Мы делаем все по мейлу — обычно я не поклонник интервью по электронной почте, но в данном случае оно работает, потому что дает время подумать. Единственный человек, который предпочел ответить на вопросы не по почте, был Ник Вустер — он посмотрел на них и сказал: «Мне что, правда надо сесть и написать ответы? Может, вы лучше позвоните мне завтра в 6 утра?»

What I love about Fantastic Man is that it is still a bit of a zine – there is no fear of long texts and plenty of topics that are not exactly advertiser-friendly. Like those tips on how to avoid paying for extra luggage when flying a low-cost airline – I mean, everyone flies low-cost these days, but this is not a discussion you would ever find in a glossy.

We are not a glossy. A fashion magazine, yes, but not a glossy. We are fascinated by clothes, and this is not something men talk about very often or very easily. We have just launched a new section, Questionnaire, where we speak to men about their wardrobes. For now these are short questions, but they may evolve into longer conversations. We do these over email – I usually do not like email interviews, but in this case it works, because it gives people time to really think. The only interviewee who preferred to do it in real time was Nick Wooster – he looked at the questions and said “Do I really need to sit down and write my answers? Why don’t you call me at 6 am tomorrow morning instead?”

How do you choose your interviewees – not just for Questionnaire, but generally? Are there any people who are definitely not “Fantastic Men”?

Well, we would obviously definitely never feature David Cameron.

— Как вы выбираете, с кем делать интервью — не только для «Викторины», а вообще? Есть люди, которые точно не герои Fantastic Man?

— Ну, мы точно никогда бы не сделали материал с Дэвидом Кэмероном.

This is exactly the person I thought – hoped – you would cite as a no-go when I came up with this question!

Yes, and we would not feature Nicholas Sarkozy, we would not feature Putin. But all these are politicians. Otherwise we wouldn’t feature… Kanye West, for example. I like to think, however, that Fantastic Man is a very inclusive magazine in the sense that a lot of people can be featured in it…

— Я про него и подумала как про вашего антигероя!

— Да, и мы не поставили бы в журнал Николя Саркози — и Путина тоже. Но это все политики. Если подумать о других, то мы бы не поставили… Канье Уэста, например. При этом хотелось бы думать, что Fantastic Man — очень инклюзивный журнал в том смысле, что в нем могут уживаться очень разные герои.

— В последнем номере у вас [рэпер] Blood Orange рядом с [критиком] А.А. Джиллом.

— Именно. Нам нравится экстравагантность, но она не обязательно должна быть в лоб — тут скорее дело в экстравагантном образе мыслей. Иногда мы спорим насчет политически некорректных героев — людей, с чьей точкой зрения мы действительно не согласны — и иногда бывает соблазн поставить их в номер.

In your last issue you’ve got [rapper] Blood Orange next to [critic] AA Gill.

Exactly. We do like extravagance but it doesn’t have to be visual; it’s more about an extravagant state of mind. Sometimes we have discussions about people who are politically incorrect – people whose points of view we really disagree with - and sometimes we might be tempted to feature them…

— Если кто-то очень хорош в профессии — скажем, гениальный дирижер, — но политически сомнительный персонаж (у нас в России есть такой), что бы вы сделали? Вы бы предоставили такому человеку право голоса или пусть дирижирует?

— Думаю, пусть дирижирует. Пример, который обсуждали мы, — это Джулиан Ассанж. То, что он сделал, невероятно, но я не уверен, что это вполне правильно. Да, свободная пресса должна раскрывать политические секреты, но правильно ли со стороны WikiLeaks все предавать огласке? Все делается настолько без оглядки, как будто просто потому, что информация существует, она должна быть открыта. Я понимаю, что при наличии 50 миллионов имейлов довольно тяжело пройти по ним всем и решить, не заденет ли это кого-то, кто этого не заслуживает, если это будет предано огласке. Но я уверен, что об этом надо думать больше.

If somebody is very good at what they do – if someone, say, is a genius conductor but a politically dubious character (we have one such person in Russia) – what do you do? Do you give them a voice, or do you leave them to conduct?

I think you leave them to conduct. An example we have been discussing is Julian Assange. I think it’s incredible what he’s done, but I’m not sure it’s morally right. Yes, it is the role of free press to unveil political secrets, but is Wikileaks really doing the right thing by just throwing everything into the open? He does it in such a non-caring way, as if, just because the info is there, it needs to be shared. I am not sure this is always the case. I understand that if you have 50 million emails it might be hard to go through them one by one and decide “will it hurt somebody who doesn’t deserve to be hurt if this goes out into the open?” But I do think one needs to be a little bit more considerate.